This is the only picture I took inside the courthouse. While there were many absurd things I wanted to snap a picture of, the unimportant-ness of this and the rogue capital L really spoke to me.

Unfortunately, this post is not some salacious tell-all. The trial on which I was a juror was not anything anyone would have heard of, even if you’re local to me. It didn’t contain any surprises or shocking testimony. There were exactly no big reveals and absolutely no drama.

No, it was a civil lawsuit trial (which I didn’t even know was something that went before a jury) that lasted merely two not-even-full days.

There had been a car accident (in January 2020!) and the party that had been hit was claiming a permanent injury and seeking damages. The party at fault for the accident was not disputing her fault. The reason this went to trial (notice the lowercase t) was because a) they couldn’t reach a settlement outside of court; and b) the burden of proof was squarely on the plaintiff: why should the defendant pay if the plaintiff couldn’t deliver on their burden of proof?

The two days were simultaneously long (re: boring) and short (only a few hours each day), but oh man: being in a courtroom of any kind is like being in an English classroom come to life!

Even a trial as uninteresting as the one through which I sat in judgment was exciting for my English teacher's heart. Because, if you’ve never been in a courtroom, it is everything we teach our kids about argument but FOR REAL! With actual stakes!

And so here is how I’m thinking about taking these things with me back into the classroom and hopefully making it all a little more real for my students.

In a criminal trial, the prosecution must prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt. If there is a reasonable doubt, then the jury must rule in favor of the defense.

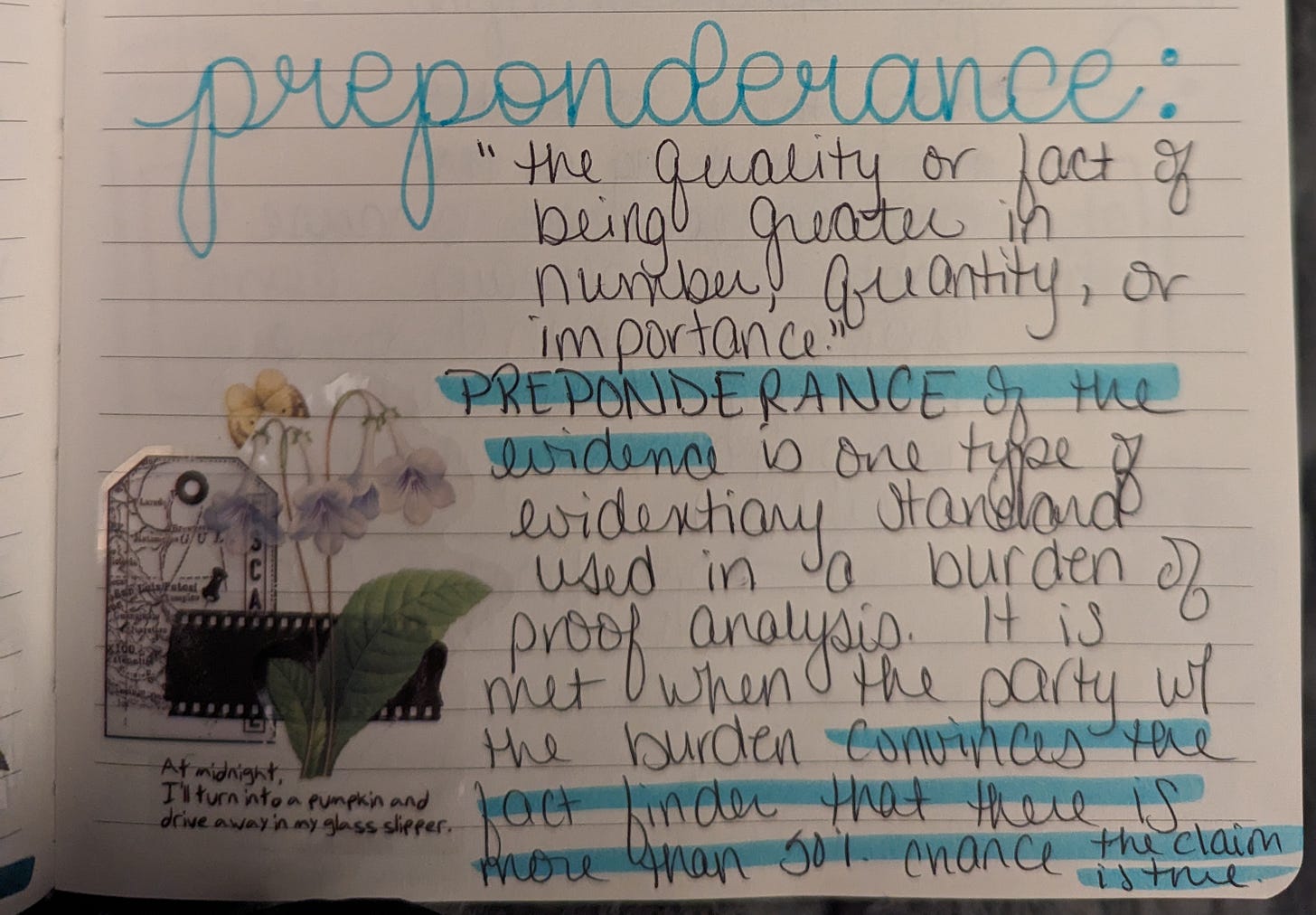

But, as the plaintiff’s attorney in my case demonstrated by making his body a scale in his closing arguments, the weights and measurements are different in a civil dispute. Instead, the plaintiff must prove their case with preponderance of the evidence. This simply means that the plaintiff must prove that what they’re saying is more likely true than not. If you, the jury, feel it’s more than 50% likely that the plaintiff is right, they win.

Preponderance might be my new favorite word and it is absolutely one I am bringing into my next argumentative unit with my students. This phrasing contains all the basics we teach our kids about strong arguments: that an argument must have sufficient, relevant evidence; that an argument relies on having evidence from credible sources; that an argument needs objective, factual evidence; and, as I’ll get to soon, that with good reasoning you can spin anything to mean what you want and with bad reasoning you fail.

Being able to present an argument with preponderance (I hope I’m using that right; the word is a noun) is important. Our kids need to know how to formulate good arguments. It is a life skill. But what I realized this week is even more important is that our kids really need to be able to smartly evaluate good and bad arguments.

Being on a jury is an exercise in evaluating evidence in order to evaluate an overall argument.

Why are we not teaching argument this way!?

It is far more likely that our students will be on juries than they will be prosecutors, lawyers, or judges. And it is a guarantee that our students will be vulnerable to being persuaded by tons of outside forces: politicians, advertisements, general mis-information and dis-information, and pretty much everything they see on social media everywhere. They will certainly be in situations where they need to present their case smartly to someone (hopefully not in a courtroom!), but they will be susceptible to persuasion every day.

Sitting with my jury-mates during our relatively short deliberation last week, we went through and weighed the evidence. We used the same terms I use as a teacher with my students while discussing the evidence. We examined holes in the plaintiff’s case. Ultimately we decided that what she was saying was a truth: she was in pain and likely would be for the rest of her life. But did she prove with preponderance of the evidence that she suffered a permanent injury? No. Her witnesses (doctors) weren’t the best. The chain of doctors she saw didn’t line up to be a convincing chain. It wasn’t that the plaintiff was lying–we just didn’t think she proved her case.

Boom. No damages awarded.

Our kids need to be able to evaluate an argument with skepticism and really, truly assess whether or not it adds up. Because, if we’re honest, arguments from politicians, from advertisements, and from weird internet news websites rarely do.

Despite my impassioned rant above about the value of prioritizing the teaching of evaluating arguments, I still learned some things about spinning good arguments. This is where I’ve always kind of shined when teaching my students how to form arguments and when debating with my father.

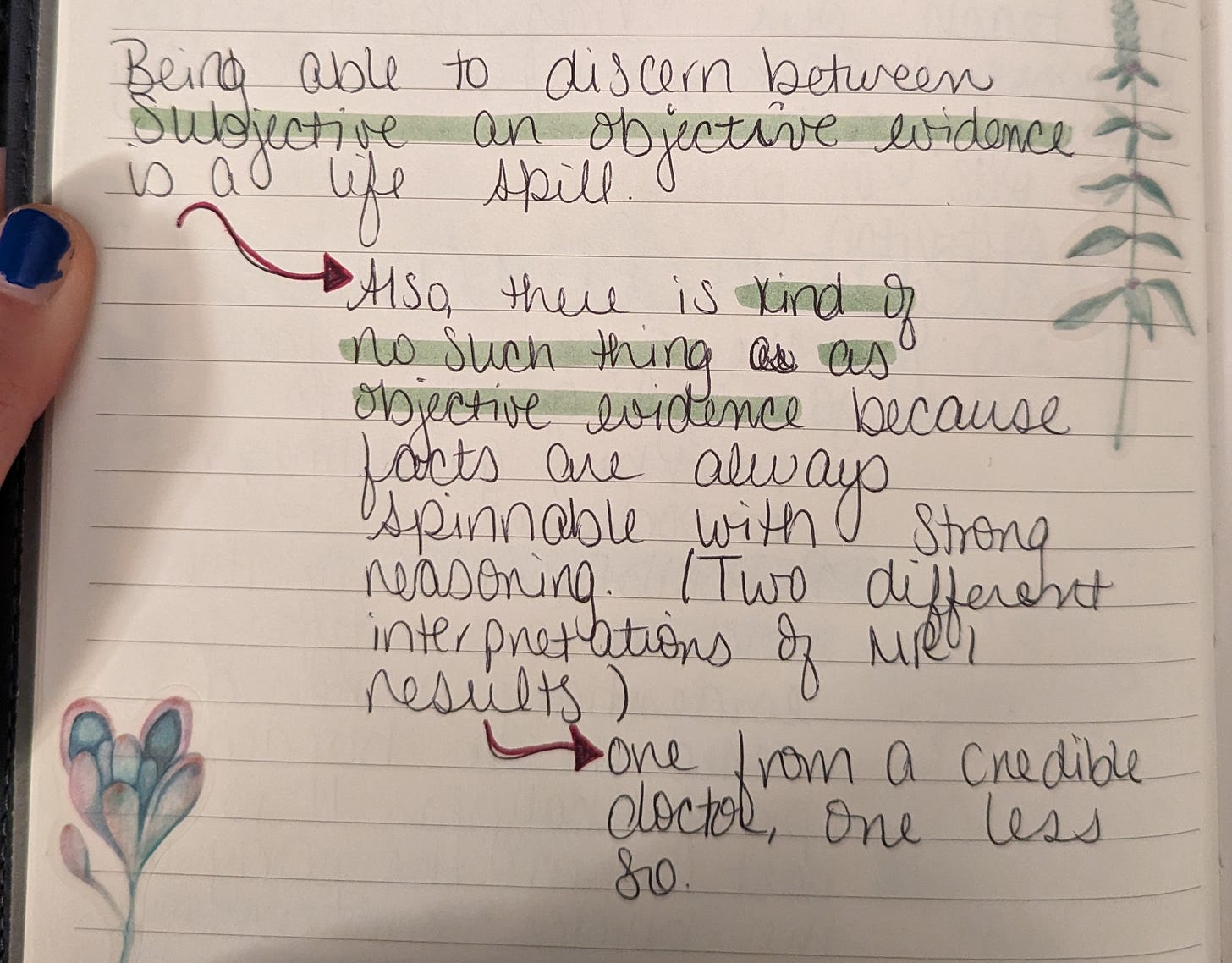

This case really came down to the testimony of a few doctors and their interpretation of the plaintiff’s MRI results. As both lawyers very clearly and painstakingly defined for the jury, MRI results are a kind of objective, medical evidence. The defense attorney, especially, really broke down for us the difference between objective and subjective. As an English teacher in the box, I chucked to myself. According to both of the lawyers, this kind of a case came down entirely to the objective, medical evidence.

And then each lawyer had a different doctor read the plaintiff’s MRI results and interpret them in two completely opposite ways. (As an English teacher on her couch, I am again chuckling to myself.) This is the kind of magic kids can unlock when writing analysis and argument if they use good reasoning. (This is also the exact kind of thing we want to arm our kids against by teaching them how to be manipulative so they can hopefully be less manipulated when others use these same tactics.)

So yes, it is obviously important that our students know the difference between subjective and objective evidence and points of view. But I think it is also worth empowering kids that they can–again, with strong and careful reasoning–make what they want to be true true. Because let me tell you: both doctors had me absolutely convinced that the way they were reading those MRI results was correct. It took a bit to decide, as the jury, who was more correct. Which is totally ridiculous when we’re talking about something meant to be seen as objective evidence!

Our kids need to know how to do that themselves so they are better armed when other, more powerful interests try to do that to them.

My Closing Arguments

In the spring, when I teach argument, I will be telling my students about my time on jury duty. You should probably do the same! I think it will make a difference. There is, and has always been, a disconnect between what we do in classrooms and the relevance students see those exercises having in their real lives. Despite being a good kid who worked relatively hard in high school, I also failed to see the connections at the time. It’s normal.

I’m not suggesting all of our classrooms should be jury training grounds, but rather that sharing jury or other courtroom experiences with our students can help bridge that gap between what we’re doing and the real world application. If you’ve not been on a jury, I’m sure you know someone who has. Lean on them. Plus, you now know me and my very underwhelming experience on a jury.

This isn’t to say that a courtroom is the only application for these skills; I just think it’s a really great and simple, concrete example for our kids to understand why this stuff actually matters. Plus, it naturally leads into the smaller, but more prescient, ways these skills are relevant. Again, we all need to arm ourselves against unwanted political persuasion, bad advertisements, and mis- and dis-information.

Evaluating arguments is probably one of the more vital life skills we teach as English teachers and so we need to teach into it hard, especially in our digital age, and make sure the kids have fun doing it (re: let them be crazy manipulative) so they can take these lessons with them when they leave our classrooms every day.

Also, I’m going to try to find a lawyer to come in and do some sort of workshop with my students. If you have access to a lawyer, start creating a strong, persuasive argument with objective evidence from credible sources now to convince them to spend time with your students, too. What lawyers do and what we try to teach students to do is the same. THE SAME. So why not bring in an expert whose voice the kids won’t accidentally ignore because it’s novel and new, and who can add some pizzazz and real world significance to these kinds of lessons?

Lawyer or no lawyer, as I start to create classroom materials around this thinking, I will absolutely share them all here. In the meantime, I wanted to share these initial musings because I really did find being on a boring jury kind of inspiring.

I was thinking about arguments when I read Dopamine Nation recently - it felt like the author was really spinning information beyond what was there in the actual evidence. I thought I would like it and ended up hating it for that reason!

Now I really want to get chosen for jury duty! Even if it is boring.