DISCLAIMER: I am already a huge fan of Dave Stuart Jr.’s work and I subscribe to his blog. I recommend you do the same; talk about generosity! His blog is rich with insight and value for ALL secondary teachers, not just English teachers.

I want to write about this book that I quite literally just finished because writing helps me synthesize my own thinking and learning (duh) and because I think this book is extremely worth sharing. It’s a quick, practical read that we can all benefit from, and I want to make sense of it while it’s still fresh in my head and I’m excited about it.

Like I said, Stuart is generous in the work he shares. In fact, when you go to his blog, the first thing archived there at the top for you are free guides to every section of his book. Yep. He even says he recommends you buy the book, but offers these extra resources if you want to go the free route. Again: incredibly generous. So while I’ll summarize some things here for myself, I seriously recommend you checking out the free resources he has already compiled to support his own work. I won’t say any of it any better than he does.

While The Will to Learn doesn’t start with the Five Key Beliefs and this super handy pyramid, most of the book and the work in it is all about this pyramid. You can read more about this here and here.

In short, this pyramid is how we teachers can build student motivation. Because ultimately, he argues, this is our job. It’s cool when students come to us already valuing learning, struggle, and our specific subject area. It’s cool when students come from print-rich homes and from families that value education, learning, and growth. But this doesn’t always happen, and that’s okay. Because it’s our job to do this work. And I agree with this mindset.

I think it’s too easy (certainly for myself) to rest on the frustration that kids just don’t care or kids don’t care like they used to or we’re teaching at a time when schools are being ultra-politicized and nobody supports me. These are stories we tell ourselves. This is a story I’ve been telling myself since fall 2021, when the shifts we’ve all noticed coming out of Covid really became clear to me.

What I see in my classroom is that students are more attached to their devices than they ever were before, and they always have at least one airpod in. What I see in my classroom is that students seem to struggle sitting in discomfort or struggle of any kind—they seem to be struggling to sustain attention or focus for long periods of time.

So then, because of these observations, I tell myself certain stories. Kids are addicted to their devices (this one might be true as we’re learning more and more about how these devices and social media work). Kids don’t care about what I’m trying to teach them and, in fact, they’re tuning me out by keeping their airpods in. Kids aren’t motivated to learn or to do well. Or, kids don’t know how to learn or do well in school anymore. (I often say kids don’t remember how to student, like it’s a verb).

But these are just stories. Stuart makes the point (many times throughout his book) that kids do actually want to learn and that we need to avoid making these kinds of assumptions. I know I definitely needed that reminder.

ANYWAY, so the pyramid of the Five Key Beliefs are how we can start to teach and build student motivation in the souls and hearts of our students.

Here are some of my other key takeaways from the beginning sections of this book:

“We develop the mind [of students] by helping students to grow in mastery of the disciplines and the arts [we teach]” and that in order to do this, we need to know our lane (4). “The intellect is our lane. If we miss it, we sabotage the relay race” (5).

If you’ve followed me in any space for a little bit, you know I am a big believer in finding ways to incorporate SEL into our classrooms. However, Stuart makes an important point here that I have definitely lost sight of. The more we’re asked to incorporate into our classrooms, the more we’re spread thin and away from the intellect, which is our main job. A lot of people in kids’ lives can and will take care of their physical, emotional, and social needs. We should still attend to them! But that is not our primary lane. Our primary lane is the thing we’re most good at, the thing we’re most knowledgeable in, the thing we’re most trained in: our content and nurturing the intellect of our students.

Student motivation, and therefore success, must come from within to be meaningful. Dangling carrots, or punishing missteps, won’t get us long term results.

Our current system is rewards-based: grades and future accolades is what kids get by learning and doing well in school. Students “want the stuff that educational success gets them—the degree, the salary, the job—while not being all that interested in the education itself. […] [S]uch a person […] is actually a poorly motivated human soul” (7).

Learning is all about deliberate, careful practice, and it’s this basic mindset we want to seek to cultivate in our students. Here are the three steps of deliberate practice:

Identify a specific subskill that incrementally challenges you

Practice that skill with full effort

Seek feedback on what you could do better (8).

Motivation comes before deliberate practice (9).

How I’m Applying This Thinking in My Classroom:

I teach in a workshop style. This is how I was trained in college, and then teaching middle school for 10 years, it only made sense. I actually was asked to teach high school in my district for this reason as our high schools are working more towards this model.

This style and philosophy naturally lends itself to a lot of the philosophy and strategies in The Will to Learn.

I do not explicitly explain what this means to students. I assume that, coming from middle school (I teach freshmen) they’re already familiar and will pick on the styles, routines, and expectations. For two years in a row, I have been spectacularly wrong. In many ways, and for many reasons.

Next year, what a workshop is is going in my syllabus and in my opening day presentation. I want to come out explicitly explaining…

That a workshop is a place where things are being tried, people are experimenting, and that it’s the experimentation that leads to learning.

That the process of the work we’re doing (writing the essay, reading a book) is valued more than the product (finishing and turning in an essay, finishing a book). Because the learning happens in the process. That is where we need to focus our attention. And then, as a result, focusing more on the process of the work will almost always yield a better product, anyway.

That experimentation is valued more than perfection.

That more attempts means more practice, and that more practice means we’re more involved in the process. Starting over, or doing another is never punishment; here, it’s an opportunity. Sometimes, the thing that feels like more work is actually the easier and better thing.

That a grade is a measurement of how we are working towards mastery of a given skill, not a measurement of work completed. So, if you’re not turning in work or you’re turning in work that’s done half fast, you’re not working towards mastery. If you’re turning in work that demonstrates great effort and growth, you’re working towards mastery.

How I’ll Build Credibility, the First Key Belief

You can read more on what Stuart has to say about credibility here.

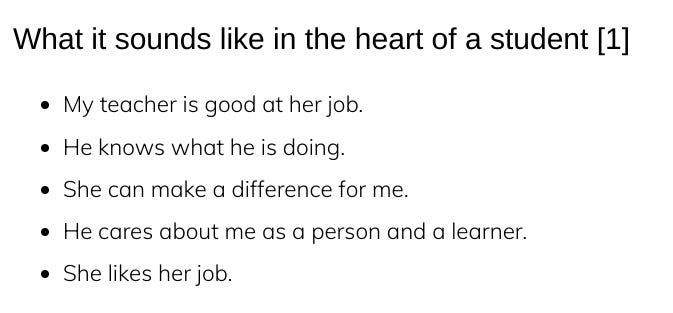

In short, if students don’t find us credible, they will never be motivated in our class. Credibility, according to Stuart, means that kids see us as being good at our jobs. This means that we are both knowledgeable and caring. It is this belief in OUR credibility that serves as the core foundation for student motivation in our classrooms.

The first strategy Stuart shares if to track MGCs, or attempted moments of genuine connection. I bolded the word ‘track’ above because I definitely do not do that and it is clear to me I need to. I need to make a greater effort to connect with the students who are harder to connect to—the ones that appear unmotivated, the ones I don’t have much in common with, the kids who are “difficult” or “disengaged.”

I regularly conference with kids about their reading lives, the work they’re doing, and things in general. By tracking these, and tracking which are academic and which are personal, I know I can maximize the work I am already doing in this area and hopefully appear more credible to more students. I’m just going to keep a clipboard for these and make sure I cycle through them regularly.

Otherwise, I’m going to just keep being weird and and making the fact I love what I teach as visible as possible to the kids.

How I’ll Build Value, the Second Key Belief

You can read more about what Stuart has to say about value here.

Of the five key beliefs, I think this one is my favorite. Stuart’s argument that credibility is the foundation for motivation makes sense, and I think I generally am a credible, caring teacher and my students (even the ones who “hate” my class) seem to reflect that back to me. For me, I know value is where I can get a lot of return on investment. It is here where I see, in my own classroom, at least, a lack. Based on observable actions from my students, it often seems like the work we’re doing in English class is not being valued.

I love the above “Rainbow of Why” that Stuart includes in his book. These are the things that lead to value, and so it’s these things we need to try to make plain to students in the ways we teach. He starts, though, with a really valuable point: in the American education system, we over-emphasize, to the point of detriment, utility and relevance as the means of value. And this makes sense given our history and our culture (I’m thinking of Emerson’s “Self-Reliance” here).

Why relying on utility for value falls flat:

Utility focuses on the future self. And while when kids ask, “When will I ever need to know this?” they’re asking about their future selves, those answers aren’t actually motivating. Stuart likens this to diet and exercise: knowing I’ll feel better in 10 years for good choices now doesn’t really make me want the ice cream any less in this moment.

Not everything we do in schools is inherently useful to our future selves in a tangible, quantifiable way. For example, telling a student they’ll need to know geometry in case they build a deck later in life is only useful if they do, in fact, go on to build a deck later in life. Speaking from personal experience, this is a hard sell. (I have not nor will I ever build a deck.) That doesn’t mean, as much as I didn’t like geometry, it wasn’t valuable. Diverse base knowledge comes in handy regularly. And all of these different disciplines we learn in school simply help us to think in different ways.

Why relying on relevance for value falls flat:

Simply, it’s too subjective! No whole group of kids will find the same thing immediately relevant to them personally. And sure, there are some choices we can make that are more timely and topical, but that doesn’t guarantee relevance in the hearts of our students.

The old person trying to be relevant and cool is pretty transparent for young people.

Relevance gone wrong can be alienating, thus hurting the value of a lesson as well as our own credibility.

Stuart says this about relevance, which could not itself be more relevant: “… in an Internet-saturated culture like the one we teach in, is an individually relevant education truly the best possible good we can provide for our students? I say let the algorithms matter individualization; let’s focus in school on mastering the disciplines” (109). This statement becomes only more relevant as we sit on the advent of wide-spread, personalized AI tutors for all students.

Instead, we need to make sure the lessons we design and the ways we teach them hit on all the colors in the Rainbow of Why.

His first strategy for this he calls Mini-Sermons. We’ve all done them: those 30-60ish second rants about why something we’re doing is awesome or exciting, often to the eye-rolling of our students. Stuart argues that by including these regularly in our lessons, and being mindful to include them in ways that hit on different paths to value, that we can explicitly inject value into our lessons. Not everything has to be discovery; it’s okay to come out and tell our students why something is valuable. In fact, we have to if we have any hope of them seeing the value for themselves in time.

I am going to start adding this to my lesson plans next year. (I know, that sounds insane: who wants to add something to their lesson plans.) But I want to make sure I am consistently thinking about the value of each lesson so I can make sure that most days, I am including that value more explicitly.

Another strategy in this chapter is called Feat of Knowledge, meaning teach lots of stuff. This is also something I used to do more often but I have gotten away from in recent years. Honestly, because I became self-conscious in recent years when I saw what felt like less engagement, especially as a high school teacher.

Stuart describes this strategy as just bringing in lots of stuff that we know. Kids won’t see value in little bits. They need to be exposed to a lot of things and aspects of our discipline in order to find value in it. So we need to teach more things. And we need to organically share more of how our discipline looks out in the world. So bring in that video or article that relates to what you just did in class. Make time for it. Nerd out. Get excited.

I am going to make a conscious effort to bring this part of myself back to my classroom next year. I don’t need to feel insecure about loving what I teach and having a lot to share. My kids lost out as I developed those feelings. Once we invite students to a feast of knowledge within our disciplines, they can find the value in it for themselves.

Which leads to his last strategy: Value Within. This is finding ways to incorporate little activities that invite students to articulate the value in what they’re doing in your class. This can be done in conferences, in small groups, or in independent writing activities. These can be quick or long, loose or structured. And yes, these kinds of activities are definitely happening in my classroom next year. I’ve already been thinking about revamping the way I use quick writes and that time at the beginning of class to make it a little more concrete; so including prompts like these periodically really fits in with that.

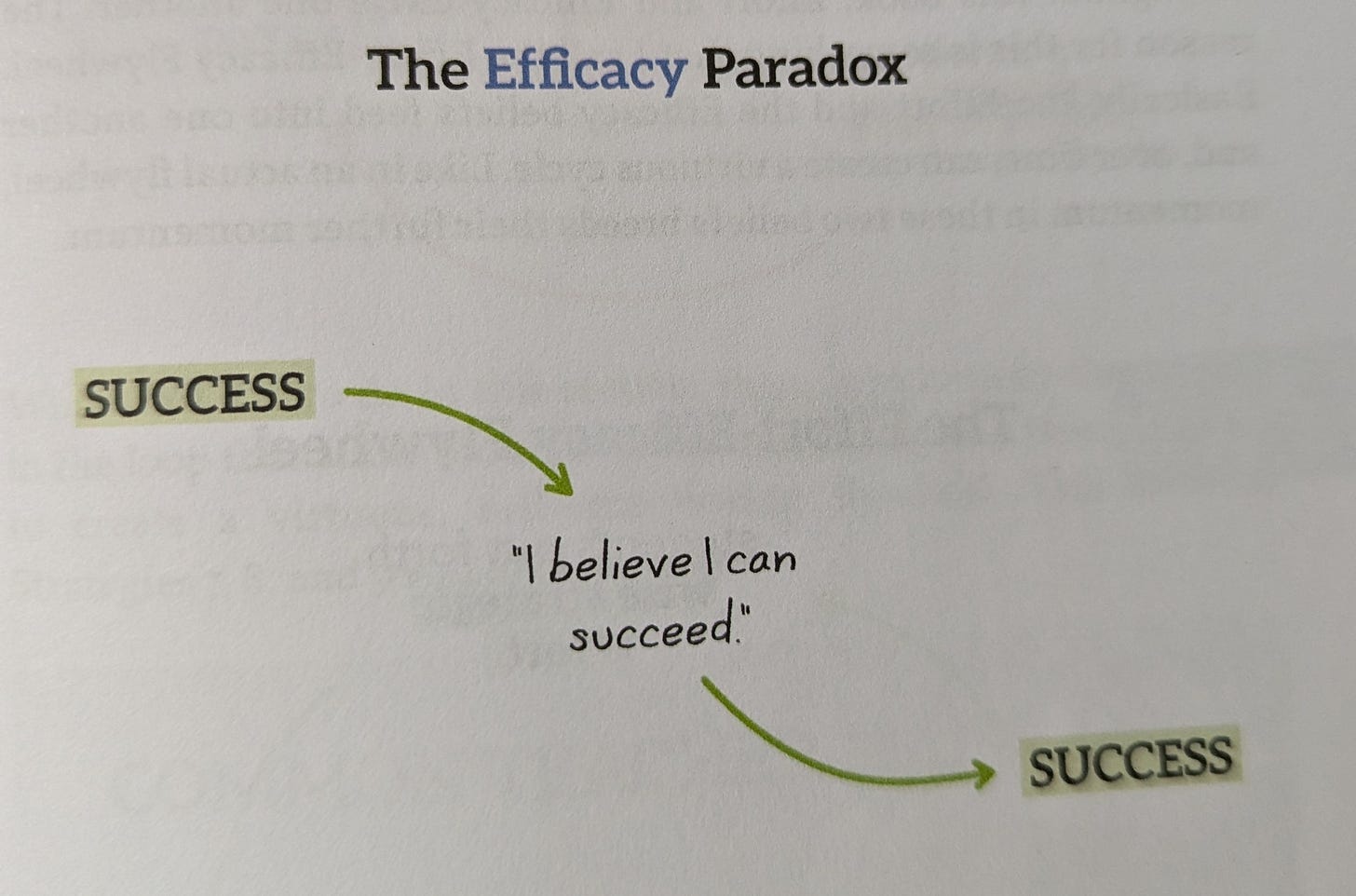

How I’ll Build Effort and Efficacy, the Third and Fourth Key Beliefs

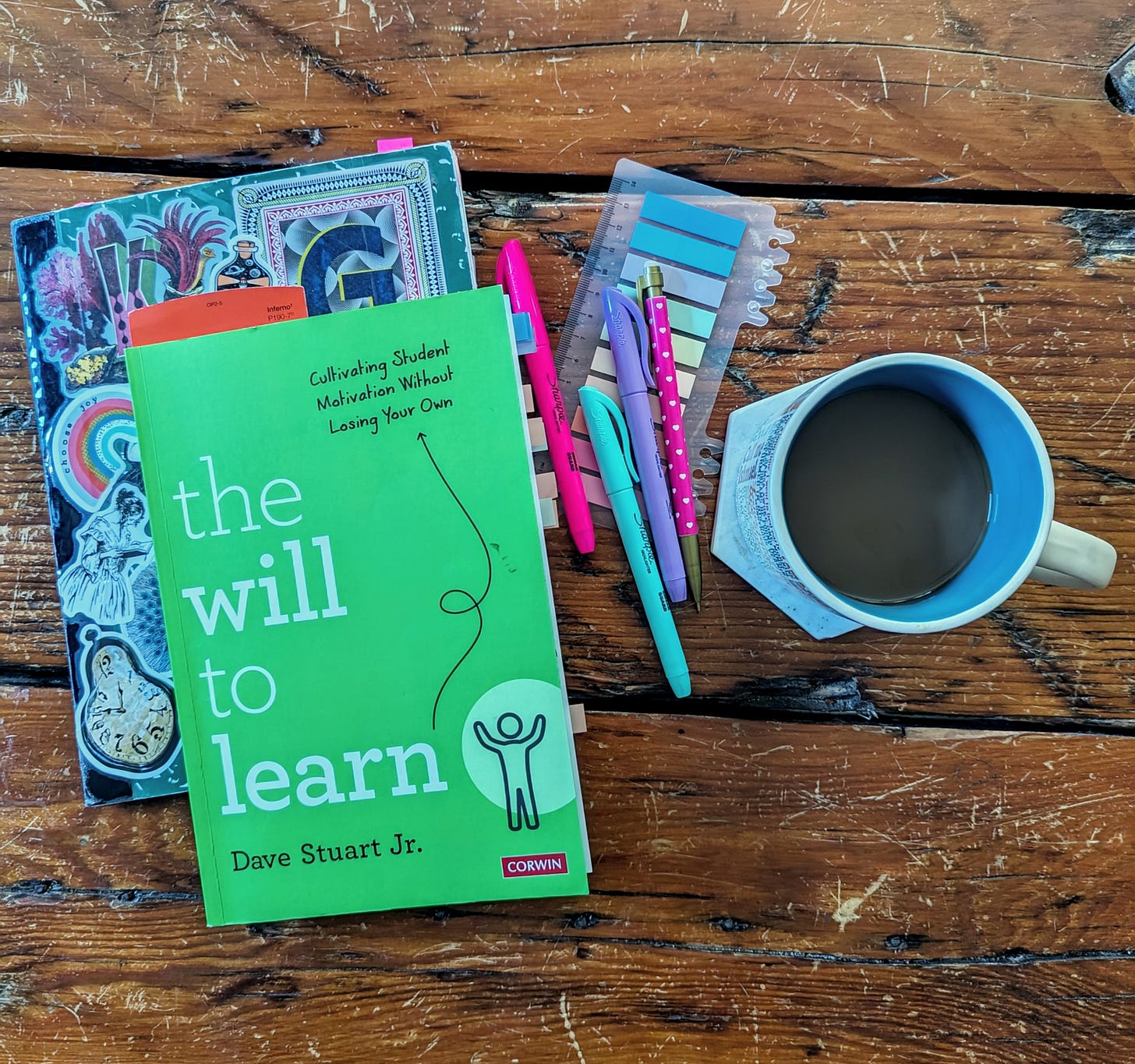

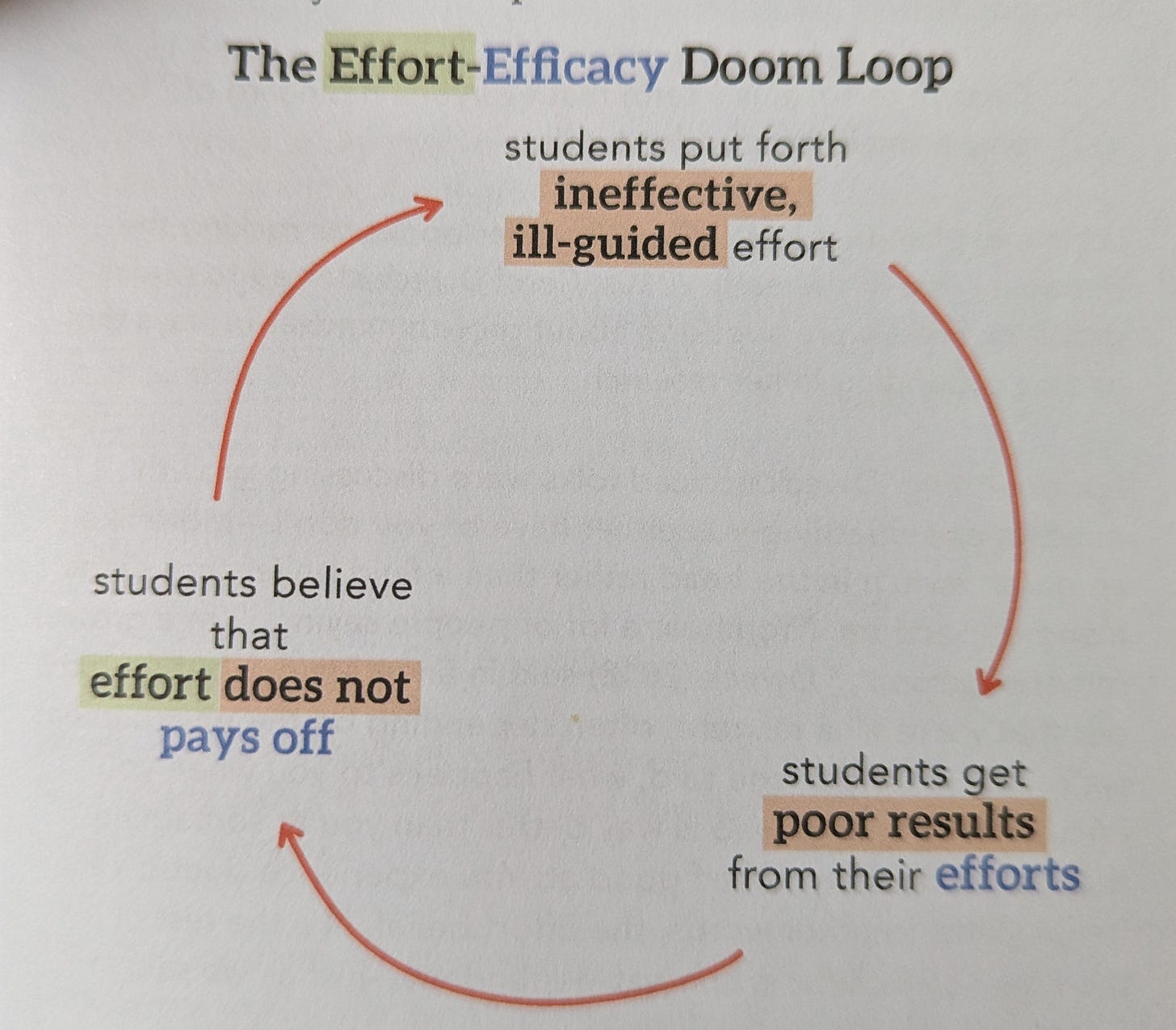

You can read more about what Stuart has to say about these beliefs here and here. You’ll see in his free resources, he has these as separate ideas, but in his book, he combines them because when done well, they create a positive feedback loop. Effort leads to efficacy, and efficacy leads to increased effort.

Like so…

In order for any of this work, it is up to us to be really clear in our instruction and expectations. We need to clearly and explicitly define what success looks like in a given lesson, unit, and school year. More so than we already are. Kids need to know exactly what wise strategic effort looks like if they’re going to even attempt to put that kind of work into what they’re doing.

I already keep a section on my daily agenda slide for the goal of the day. I’ll definitely be giving more attention to the daily goals I write and instead of just leaving them there projected, I’ll be going over them at the beginning of class. Then, at the end of the lesson, I’ll have the last slide with the explicit asks/next steps for students’ work time as well as a reiteration of the goal. I will do this with more consistency than I already do. If I want my kids to put in the effort, it is my job to define what that effort should look like and what they’re effort is working towards.

This also leads to my favorite of Stuart’s strategies in this book which I feel genuinely excited to try: Woodenize All of It.

I was first introduced to this idea in a blog post from the winter, before I started reading this book. Stuart wrote the post about a math teacher who always taught his students how to use a calculator in the same way that Coach John Wooden from UCLA famously taught his athletes how to put on their socks and tie their shoes.

Immediately I made a list of the kinds of things I needed to Woodenize, the things that I take for granted and assume students know how to do already:

How to use a bookmark

How to capitalize properly

How to start reading a new book

How to organize a notebook (meaning, to always add a date and heading of some kind)

The basics of MLA format

How to write in paragraphs

That they should gather all necessary materials before class begins

Submitting an assignment as soon as it’s completed

And then after reading this book, I added some “biggies” to this list, things that I’m teaching kids now but need to more finitely break down as if it’s completely new and that will need constant reinforcement:

How to annotate

How to synthesize when reading new information

How to read better (to read longer, to read more, to get more out of what we read)

I immediately knew what to put on my list because they’re all things I’ve been surprised by kids not knowing how to do over the years, like using a bookmark. If you don’t really read ever, of course you don’t intuitively know to use a bookmark. And if you’re always having to find your spot and start over or are missing things, of course reading is more of a chore. So I need to Woodenize that practice which is so foundational to students’ success in my class. More kids need to hear it than I think.

And this dovetails really nicely into Stuart’s last strategy in his book in the Belonging chapter.

How I’ll Build Belonging, the Fifth Key Belief

Belonging is at the top of Stuart’s pyramid because it is the last thing we need to build. It depends on everything that comes before it. You can read more of what he has to say about belonging here.

As with Woodenization, I was first introduced to the above idea in one of Stuart’s newsletters, aptly titled, “Next Year, Don’t Start with Belonging.” When we do this, we’re doing it backwards. And we often do this backwards. It’s kind of what we’re trained to do, especially teaching younger students. We’re encouraged to refer to students as “readers,” “writers,” “scientists,” “artists,” but this is putting the cart before the horse. Calling a kid a reader (or a writer, or a scientist, or an artist) won’t make him see himself as a reader; but proving your credibility, adding value to the work, showing kids how to put in the effort so they can be successful: that will help him see himself as a reader.

If we’re doing all of the other things right, Stuart argues, belonging is already happening for our kids. Stuart carefully outlines how each strategy in his book also feeds into students’ sense of belonging before offering up one last strategy to explicitly target this key belief: Normalize Struggle.

(Don’t mind my notes there in the corner.)

When we normalize struggle, celebrate it even, we create space for all students to belong, even the ones who don’t see themselves as readers (or writers or scientists or artists).

Stuart, or course, offers several methods for this strategy. For me, I think my application will be two-fold. First, I want to make sure I slow things down next year and assume nothing. I want to make sure that when we do something difficult or new, we debrief the struggle that should have been found within it.

Second, I want to find ways to celebrate struggle. Going back to some of the first things I wrote here, I want to make clear to my students on day 1 that success in our class is in the process, not in the final product. A part of that is also highlighting that learning happens in the struggle and in the discomfort we might sometimes feel and that we should invite it in rather than shy away from it. This is also why experimentation and risk taking (in the choice of a book or who students choose to write) is valued over perfection.

I am going to make sure these things are clear on day one and that they are regularly reiterated. And then I am going to make sure that all of my actions are in line with that belief. If I am in clear and true alignment, my kids are more likely to feel safe taking those chances and sitting in struggle.