The first time I really heard about SEL was towards the end of the 2018-2019 school year. I was selected as one of a group of teachers from my school to attend a Responsive Classroom institute that summer and then to pilot Responsive Classroom initiatives throughout the 2019-2020 school year.

No, the irony of the timing is not lost on me as I look back.

I think the people at Responsive Classroom are doing well-meaning work and probably do make quite a difference in certain settings, so I won’t editorialize too much. I also think they’re a great place to start with this sort of work in that they promote an important mind shift for teachers. So I won’t be unkind. But the simple gist of my takeaway from my week of learning that summer was that Responsive Classroom was yet another packaged program I had to somehow fit into my days with kids and the puzzle of it all didn’t really fit. (I also thought that taking a program designed for elementary school didn’t naturally translate to secondary school and that much of the program wouldn’t work for my kids. This is a phenomenon we’ve all witnessed with different initiatives over the years.)

It wasn’t a total loss for me, though. This started a years-long journey into thinking about how to make SEL practical, and therefore meaningful, for both my kids and me. I am grateful that I was exposed to and worked on these ideas before the pandemic. I was able to really experiment and get a feel for what meaningful SEL could look like in a secondary classroom before the stakes felt as high as they do now.

To say that kids are worse now than they were before is a completely unfair statement that places a lot of unnecessary judgment on the young people we serve. The youth is always changing. This generation just might have changed more quickly. But to say that kids are different now than they were before is an objectively true statement. Teaching in 2024 is markedly different from teaching in 2019 because kids are different.

I think we secondary teachers–especially we English teachers–need meaningful, practical SEL strategies for our kids. We need things we can do with our kids that will truly engage them and will actually help them think about their own well-being and the world around them differently. I think this is an essential component of education and that is more important now than it has been before.

So here is my first strategy:

Incorporate SEL into your regular writing with kids.

I teach my high school English class as a workshop in the style of 180 Days from Penny Kittle and Kelly Gallagher. This means that we do a daily (or almost daily if we’re being realistic) quick write. In this style you present your students with a seed out of which their daily writing can grow. A seed is meant to be something that inspires writing and something students write beside rather than a traditional writing prompt.

For example, you might give your students a poem and they might borrow a line from that poem and write off that line, or they might write their own version of something they see in the poem. Or, you might give your students an interesting chart from a recent study and kids can write in response to it.

This is not how all of us do daily writing with kids. Whatever your routine looks like, whatever kinds of prompts you give (or don’t give your kids) for regular writing, you should replace some of the things you usually use with kids with things that promote SEL.

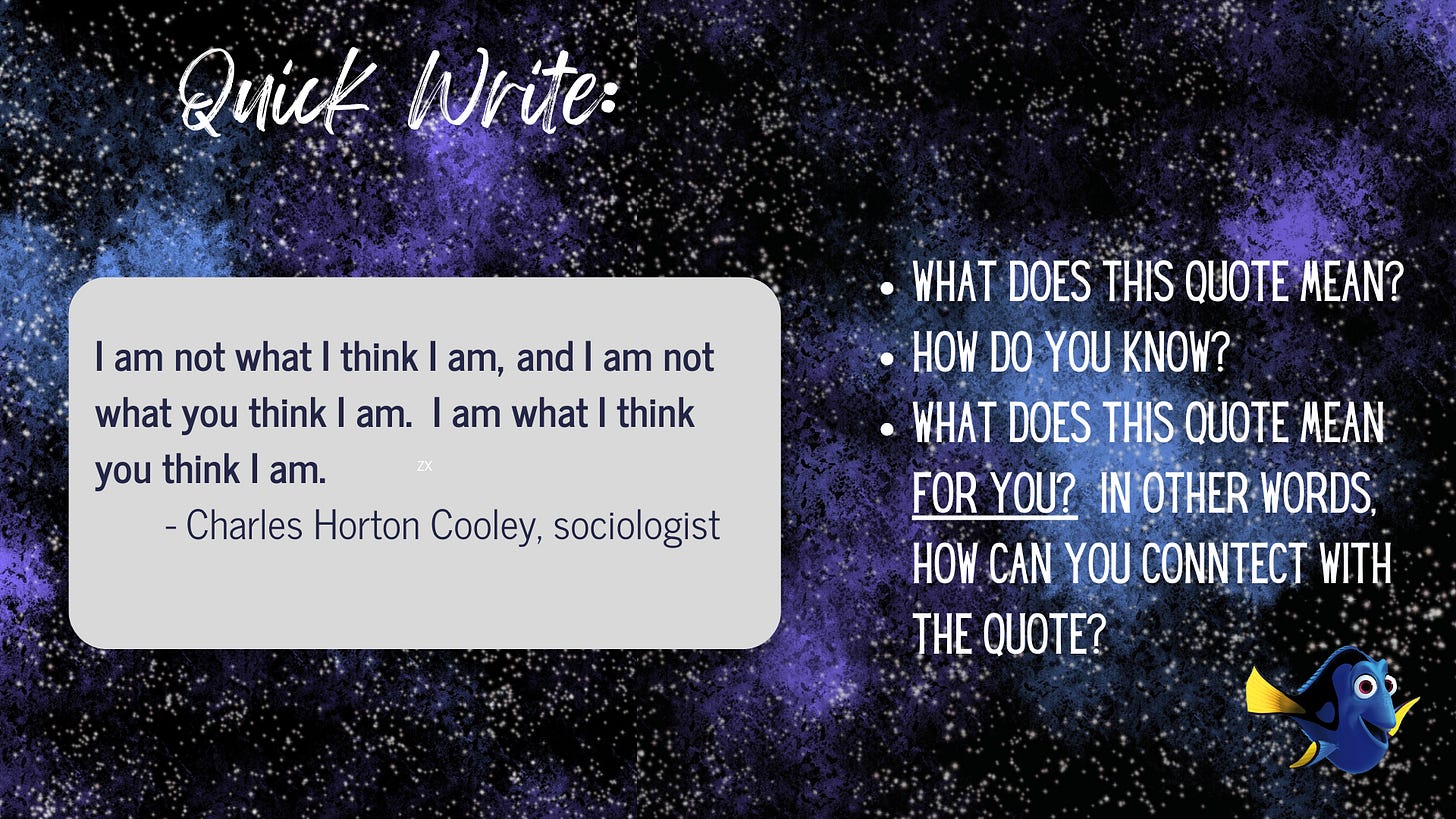

For example, here is our quick write from Monday:

We were reviewing analysis strategies Monday, and so this quote served two purposes: first, a quote analysis is a great, quick way to practice analysis. But more importantly for our purposes here, this quote got kids thinking about how they form their own identities and the ways they view themselves. The ways we project things on others and the ways we make assumptions about others. The ways we internalize things that may or may not even be grounded in reality.

Is this the best way to teach these ideas? Probably not. It’s quick! We’re touching on these ideas quickly before moving on to another thing.

But this is a way to bring up the conversation with kids that doesn’t take away from the other 1,000 things we have to do in a day. And because this doesn’t take away from the other things we’re responsible for, we are able to do this with fidelity. I feel like we are all guilty of starting a new thing with our kids, and really starting strong, but then after a little bit we drop it. It just doesn’t maintain. I am guilty of this, at least. (See: most ways I’ve ever taught vocabulary.)

But bringing in seeds or writing prompts with an SEL bend to them is easy to maintain if you’re already doing quick writes with your kids!

Another reason this strategy is so practical and manageable for us is because it makes the subsequent conversations seem very approachable. I know an obstacle that many of my colleagues experience with this work is feeling like they are not trained to do this work. We are teachers, English teachers, not psychologists. What if we say the wrong thing? So when we incorporate these conversations in our regular quick writes, we keep them manageable enough in scope and severity that we can rest assured our training is enough. We’re smart humans who read and who know how to work with kids: we can talk about identity formation in a short burst without worrying we’re doing harm or generally biting off more than we can chew.

Not sure where to find these seeds? Be sure to subscribe so you can see next week’s newsletter where I will provide a roundup of quick write seeds that promote SEL.