Adam Grant is the best. If you’ve ever heard him speak, you’ll hopefully understand what I mean: he always sounds like he’s smiling while he talks. Between his TEDTalks, his podcasts, and the many interviews he gives, it’s easy to hear what I mean. (He’s been a repeat guest on Armchair Expert and those episodes are absolutely delightful.) And this is to say nothing of his writing. He writes a great article for us non-academics and his newsletter is a quick but meaningful one. (I think he’s wasting away consulting with businesses instead of schools, but I also can understand that when you’re really good at something, you go where the money is. Then again, he’s written a lot about teachers and education, so maybe there’s hope that one day he and I can do the collaboration of my dreams.)

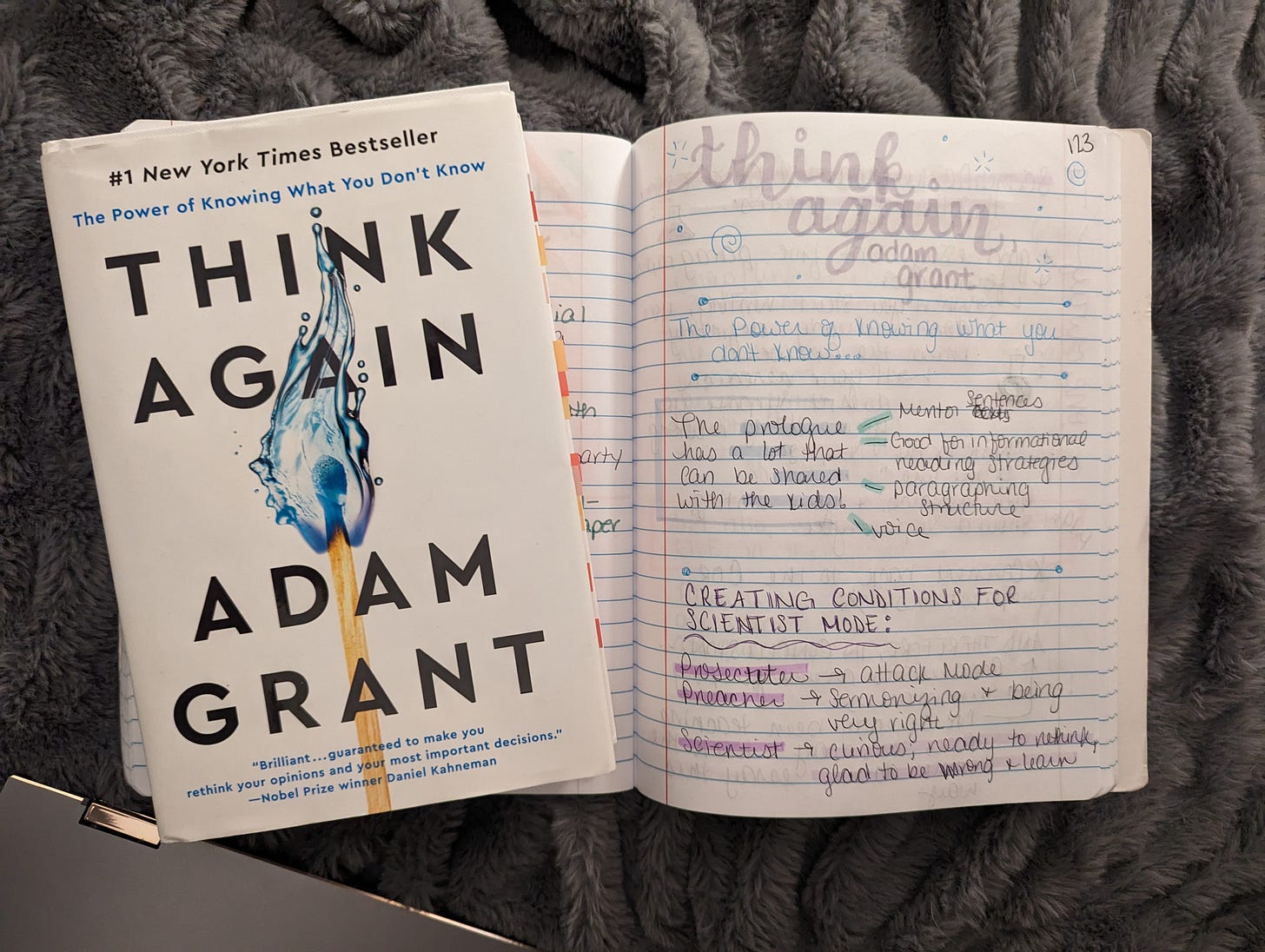

Despite being such an Adam Grant enthusiast, I admit that Think Again is my first of his books I read, and I only read it not too long ago. I started listening to it and about half way through I had to stop. I was hearing so much that was relevant to the work we do in our classrooms that I knew I needed to buy myself a copy of the book I could write all over. So at the start of the new year, that’s exactly what I did.

One of the ways this book is great for us English teachers is that it could make a great mentor text! The prologue, in particular, is a great place to pull from because then students are getting things more or less in context since you’re pulling from the very beginning.

Many of his sentences could be used for sentence study–he’s just a good writer like that.

His paragraphing structure is great. If kids aren’t writing canned essays, it takes a lot to teach them to paragraph their writing in smooth and meaningful ways. But I think Grant’s readable style lends itself to a discussion of paragraphing. Plus, he writes great transitions that truly connect his ideas from one paragraph to the next.

His writing is also a great opportunity to teach about voice, what it is, and how to incorporate it into your writing while still sounding authoritative. (I would recommend playing a clip of him speaking, too. I’ve done this with poets like Jason Reynolds and it leads to a great discussion about voice in writing.)

If you’re looking for a short, accessible informational text to read with your students, I would also recommend the prologue to this book. I think the main thesis of this book is extremely relevant, especially as this election season really ramps up, and so the prologue would be a good way to tuck some meaningful food for thought, perhaps even conversation, into an informational text lesson.

Since I know we all love a good, practical professional book that we can take from to use in our classrooms the next day, it’s also worth mentioning that this book, despite being theory-based and not specifically for classroom use, has a bit of that, too. The last section, “Action for Impact” provides a sort of outline or overview of the book, a concise summary of the strategies from it, and action steps for that strategy. It’s a fabulous resource.

But the really good stuff is what’s in between those more immediately practical sections.

Chapter 1 is called, “A Preacher, a Prosecutor, a Politician, and a Scientist Walk into Your Mind.” (See what I mean about voice!?) In it, he defines four different kinds of mindsets or stances people tend to take. A preacher will do just that: preach. They are right, they have figured it out, and they are going to tell you about it. A prosecutor will put their ideas out there while tearing down your own to prove that they are right. A politician does what politicians do: they schmooze and double down hard. But a scientist approaches with a critical, curious mind. A scientist will see being wrong as an opportunity to learn more. A scientist asks questions and seeks answers. A scientist knows what they don’t know, or at least, they’re open to finding out they may not know what they thought they knew.

Grant argues we should all be scientists and approach life from that stance. I agree. But what does this mean for our classrooms?

It means a lot of the things we probably already cognitively know. It means we should ourselves be scientists as we get to know our students. It means we should be scientists about the craft of teaching, and teaching well. And it means we should do everything we can to create classroom conditions that cultivate this mindset in our students. We should have more inquiry-based classrooms. We know that. This all has been written about extensively and I am not really the person to add to that conversation, at least not right now.

Here’s what I can add, though. Kids need to approach their writing more like scientists–especially when writing essays.

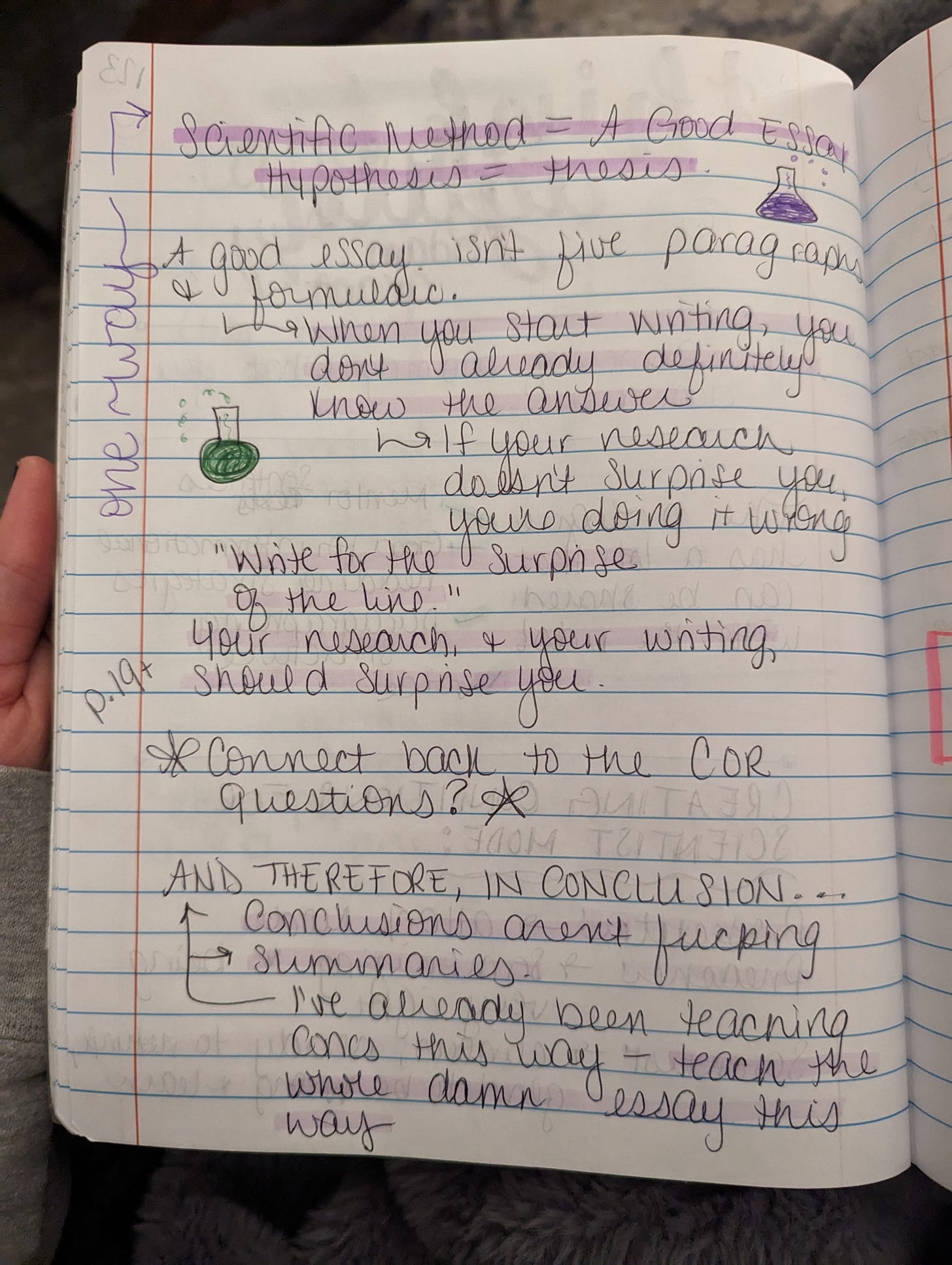

I don’t think we should be teaching students to do research in order to find information that supports their claims. I say this as someone who is absolutely guilty of having taught research and writing that way in the past. But instead, we should teach thesis statement development the same way a science teacher would teach hypothesis development. A thesis statement IS a kind of hypothesis. HypoTHESIS.

Students should go into research maybe hoping they’re right, but more curious than not. If young people–or any people for the matter–go into research looking only for what affirms them, then they’re doing it wrong.

Research, and then the writing that follows, should be about exploration. According to Etymonline, the word essay comes from the French essai meaning "trial, attempt, essay." Etymologically speaking, an essay is meant to be an exploration. When kids say they’re not sure how to write their introduction because they haven’t written their essay yet, that’s not a bad thing! Who among us hasn’t gotten to the end of a piece of writing and had to go back to the top and change things?

So in short, I think the quickest way to help our students think more like scientists is through the writing processes we invite them to take while they’re in our charge. From start to finish, an essay and the process of preparing, researching, and writing that essay is more of a science experiment than it is a predetermined writing outcome. PLUS, the bonus is that then maybe our kids won’t keep writing summaries as the conclusions to their essays? The conclusion of a lab report is the experiment’s findings and what these findings mean. The conclusion of a good essay should be the same.

Grant does discuss the writing process in Think Again explicitly a few times throughout the book. At one point, he provides a sort of case study in a teacher named Ron Berger (198-203) who is the teacher I wish I was. He teaches elementary school, and his approach to every subject in every grade he’s taught is very much an inquiry-based, many-drafts sort of workshop. He’s got little kids drafting 4 pictures of a house before they get it right AND has the kids critique each other. It’s incredible. But I digress.

One thing this section reminds us of is that writing is revising. That’s such an old idea. And if writing is revising, then writing is also rethinking. This is something we also need to cultivate in our students’ writing lives with us. It is why Kelly Gallagher collects “best drafts” from his students rather than final drafts.

(NOTE: This book is filled with incredible Venn diagrams like this one. They’re worth the price of admission.)

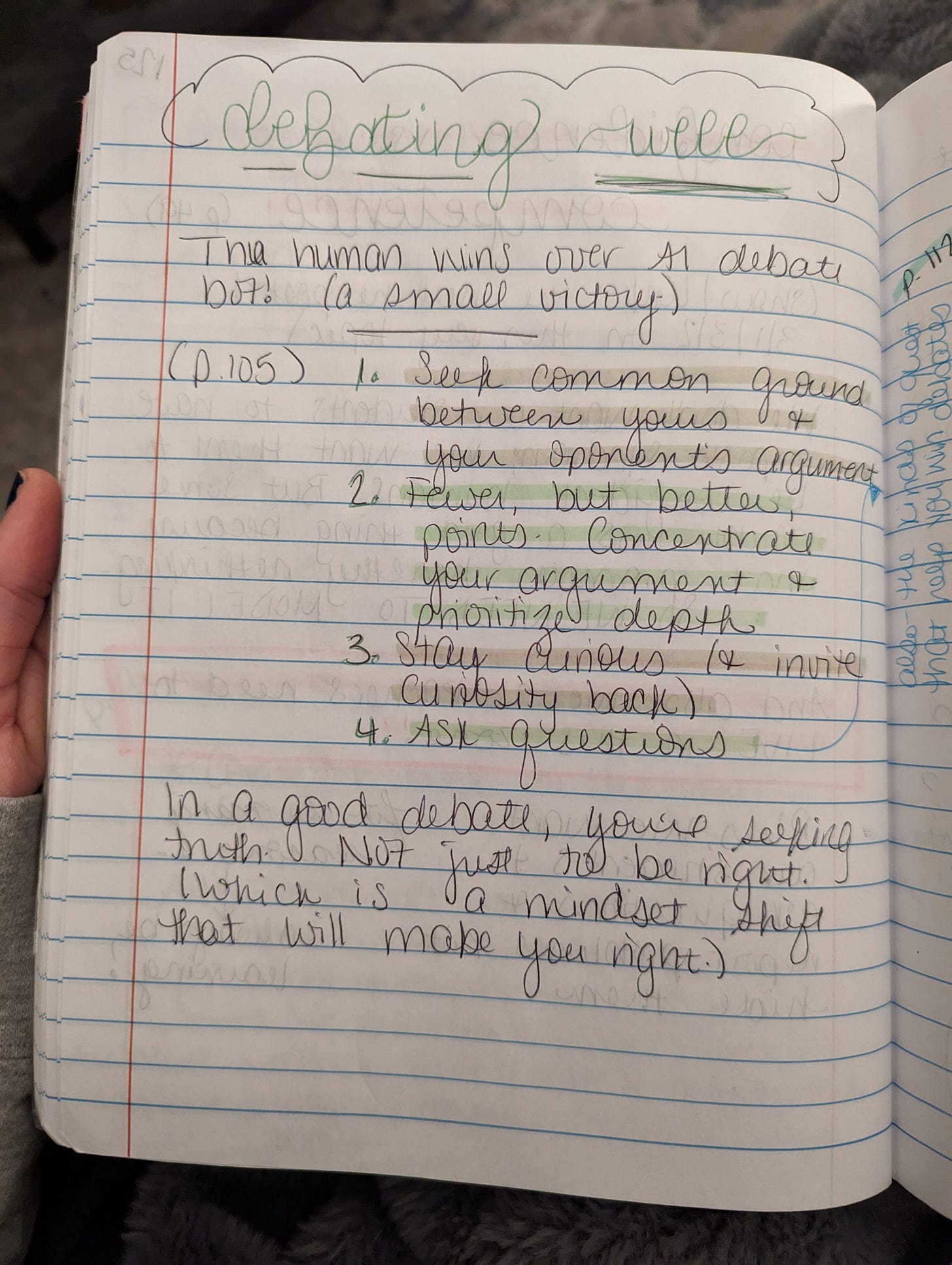

A chapter that gave me a lot of hope was, “Dances with Foes: How to Win Debates and Influence People.” The chapter begins with the story of two master debtors going head to head: Harish Natarajan–a renowned international debate champion–versus IBM’s Project Debater–the Watson of debate, or at least that’s IBMs goal for it. Luckily, Harish won the debate. (In the audiobook, Grant includes clips of the debate. 10/10.)

I say luckily and that this chapter gave me hope because in our larger, unpredictable moment of generative AI and all of the questions we don’t even know to ask let alone answer, it’s comforting to know that the human with heart won out. But more importantly, what I loved about this chapter is how and what we can learn from the human winning the debate–and how we can apply that in our classrooms.

Grant says that debate isn’t a war, or even a tug-of-war, but a dance (104). (See incredible venn diagram above.) In reading this chapter and Grant’s breakdown analysis of how victory was ultimately won, we can learn a lot about how to teach and conduct debates in our classes. Good debaters do the following:

Seek common ground with their opponent’s argument.

Have fewer points, but much stronger points. This keeps them less vulnerable to take downs and allows them to make stronger cases for the good points they have.

Stay curious and seek to invite curiosity back (debates, afterall, have an audience or judges they have to win over, not their opponent).

Ask questions.

I feel like along with other good rhetorical strategies, this guideline for debate could get kids thinking much more creatively. (I’ll let you know when I have my kids debate later this spring, hopefully under the tutelage of a lawyer!)

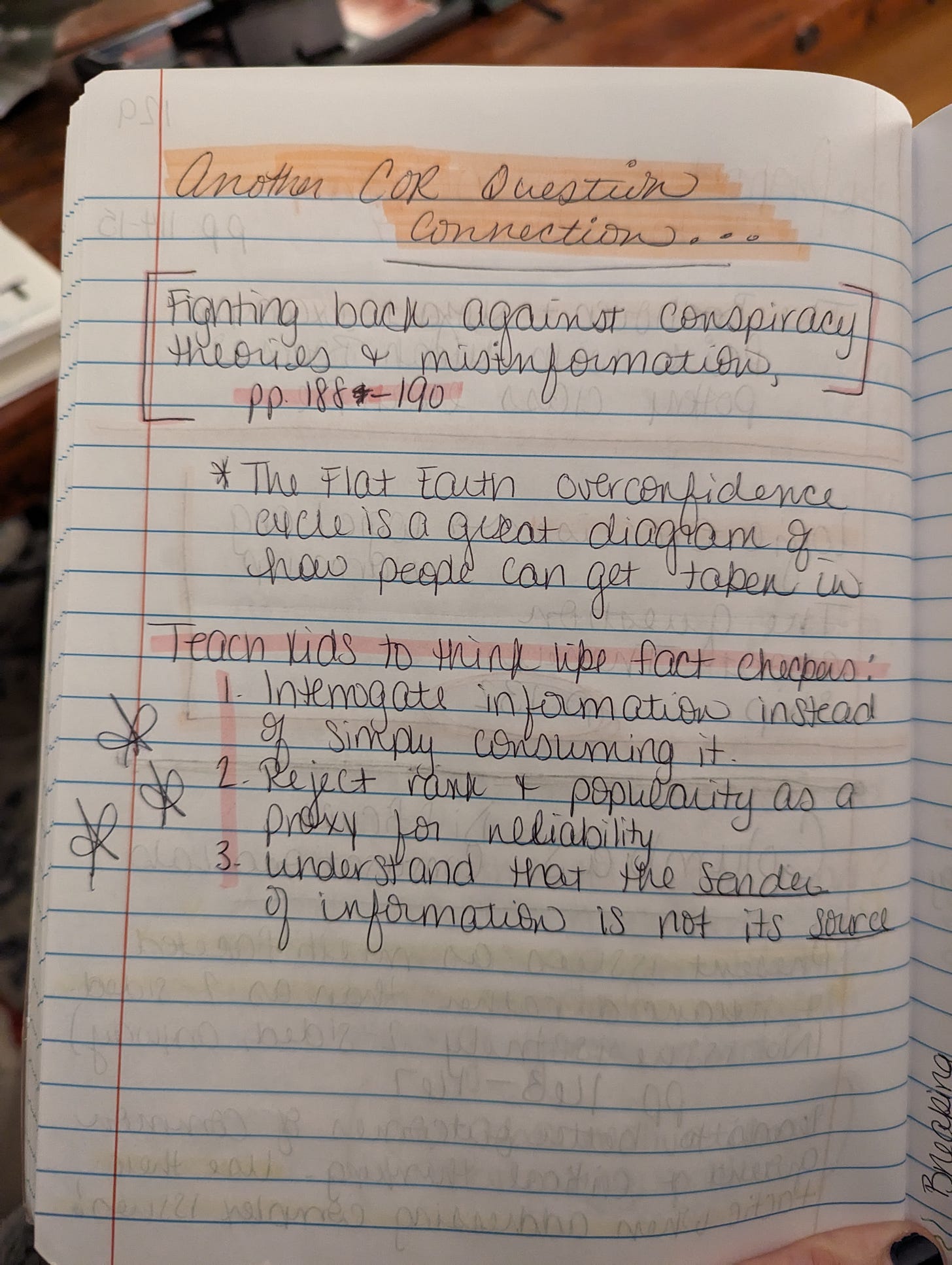

I really loved reading Fighting Fake News, a practical professional book for teachers that should really be in every classroom and required reading for every teacher. The first lesson in this book uses the COR (Civic Online Reasoning) Questions to help students quickly but appropriately evaluate information they find online. I highly recommend making a free account here and getting access to all of their wonderful, free materials. So good.

The work of fighting misinformation and disinformation is important to me as a human and as a teacher, especially to students who will be voting soon (but not November soon). Grant also provides a quick but easy framework for this kind of work that I plan to introduce to my students the next time I set them loose on the internet: Think like a fact checker.

Honestly, it’s such an obvious mindset to invite students to take I can’t believe I never thought of it this way myself before. Here’s how Grant says we can do this with our kids:

Interrogate information instead of simply consuming it

Reject rank and popularity as a proxy for reliability

Understand that the sender of information is not its source

Believe it or not, there is still a lot I could say about this book. There are things in it we can take and use in our classroom tomorrow–like the prologue and the framework for thinking like a fact checker–and even more that with time and cultivation, we could take into our classrooms next week–like turning thesis statements into hypotheses. One of those things that I myself am still trying to ponder and cultivate is how I can use some of Grant’s methods and ideas in this book to help promote kids thinking again about hating reading. I teach freshmen; at 14 and 15, they’re too young to be fixed into any identity, especially one where they’ve decided that something just absolutely is not for them.

Next week our school is testing, so I’ll have some days where things are a bit slower during which I can sit with this question. So stay tuned for what I try around using Think Again to support the reading culture in my classroom.